I wrote my artistic dissertation in 2021 at the Piet Zwart Institute. It is a 6000 word text, where I give insight into my artistic journey and shine light on my intentions and inspirations.

In the texts, written as letters to my friends, I discuss trust and compassion in-depth. I make a plea to trust that our friends’ realities are multiple and relational, and that trust and compassion are fundamental for us to become who we’re meant to be.

Weaving throughout the thesis are biographical elements to show how racism and (post) coloniality impacts myself and my friends. I make suggestions on how to continue our artistic journeys without falling into neocolonial traps.

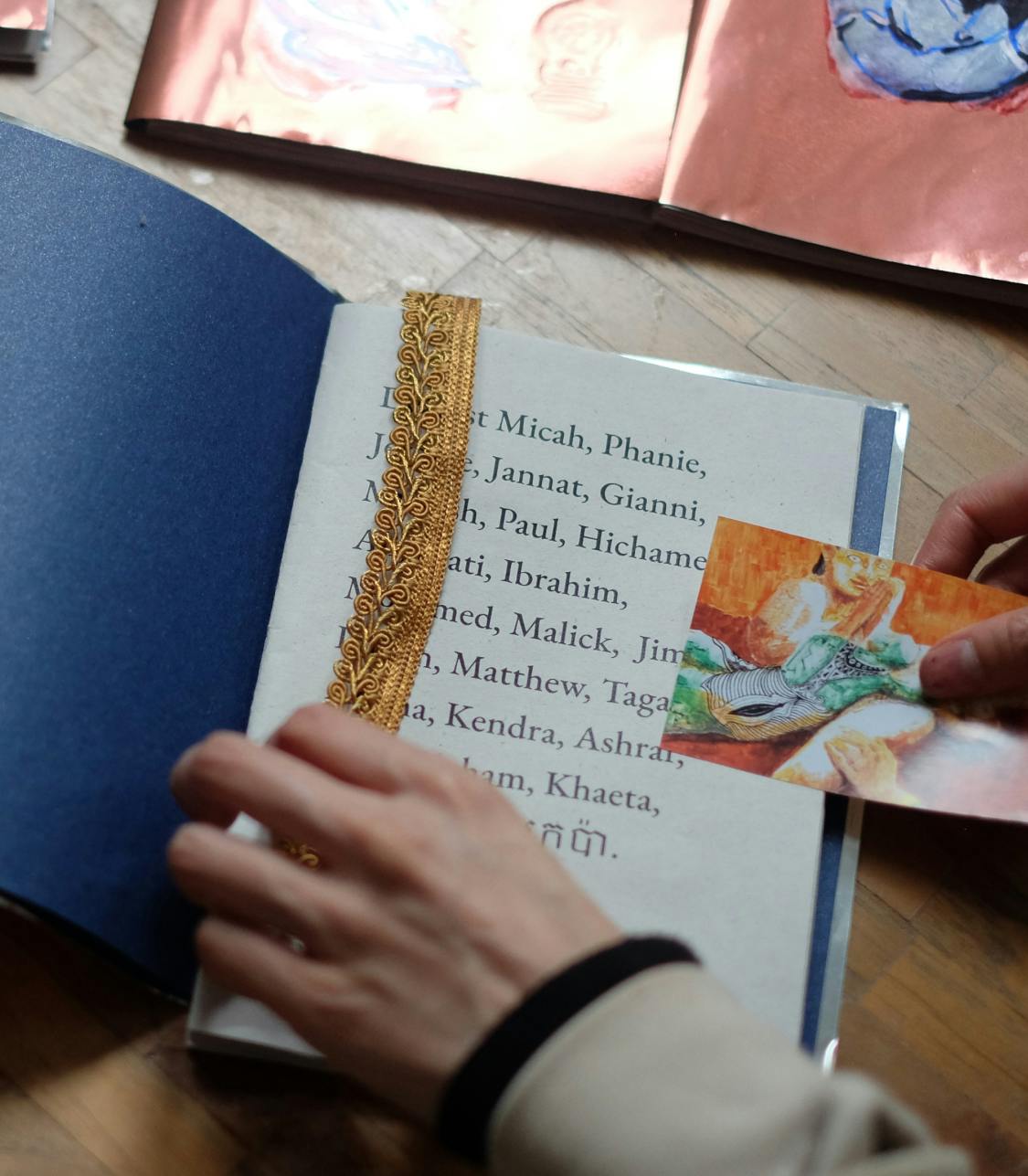

I’ve written this thesis as a grand letter to my friends who are addressed on the title page.

This is meant for them.

Excerpts (pages 4-8)

Rotterdam, 17 December 2021

Dear reader,

My name is Samboleap Tol. I am an artist. This is my artistic dissertation - a text for my Masters of Fine Arts at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. I would like to tell you my story of how I became an artist.

I came to the arts in a roundabout way. I was born and raised in Roosendaal, south of the Netherlands, to Khmer refugees (1990). My parents had been granted the Dutch nationality, though their parental styles were deeply influenced by their experiences as war children and refugees.

I showed a knack for drawing early on, but my hope to explore it further was squashed by my mother. She’d instructed my uncle to sit me down at age ten and say: “You cannot go to art school,” hoping I would pursue a traditional career in law, engineering or medicine.

After a difficult period in high school, I found my way into academia. I studied International Bachelor Communication & Media, a new course at the History department at the acclaimed Erasmus University (Rotterdam). My class was its first cohort. I did remarkably well, as I was a fervent lover of 2000s-style internet which we studied in depth, and I liked academic texts. I had all my hopes set on an exchange. Unlike my Dutch peers, it was considered abnormal for Khmers to live with other students and have ’the university experience’. It wasn’t like I longed to share rooms with strangers of my age, but I was a lover of music, and in our culture, girls were simply not allowed to go out and enjoy concerts. In fact, my father’s allegiance to patriarchy, made it so that I was forbidden to stay over at others, wear make-up, wear a side-bag or even sit on the saddlebag of a bike. My urge to leave home went hand-in-hand with my longing to express myself, which seemed impossible under patriarchy.

My first experience of living outside from home was in Sydney. I was nineteen years old and was an exchange student at the University of Sydney, Media & Comms department. This was the first time I tasted ’freedom’ even though I was renting a room at my aunt’s place in Western Sydney. I was offered a full time paid internship and a full time sponsorship at a startup and made the decision to stay in Australia, breaking the hearts of people back home.

At twenty five, I found my way back to Europe, having been made redundant at my job and unable to find a suitable sponsorship after. My parents decided to move to Cambodia the same year to start a shiitake plantation. My father had been jobless for six years. No Dutch person would hire him, despite his qualifications and years of experience as an engineer. Back in Europe, I had one mission and that was to become an artist. My work in digital marketing became unfulfilling when I discovered books on the Khmer Rouge and started unravelling why my parents were so broken. I suddenly realised why I did not have any grandparents, why so many members of our community were addicts and why I had no role models: a third of my parent’s generation died in a genocide and everyone else suffered greatly under consecutive civil wars.

I found it remarkable that I had found a way out of my household (as it was deemed impossible for girls) and that I had the literacy to read these texts. It was considered abnormal for Khmers to share their traumatic stories with anyone, let alone their children, so my generation grew up largely ignorant. We only spoke a handful of Khmer, loved American entertainment and were interested in anything that felt exuberant, because our parents put so much effort in shielding us from it.

I also found it hard to reconcile with my new identity, the one I put all my efforts in forging: independent, middle-class and Western. With time, I longed for the gregariousness of my broken and perhaps imagined community, because I discovered I had not much in common with Western, middle-class people. I shared little of their dreams and aspirations, their frustrations and problems, and even found some of their accomplishments irrelevant. Sometimes I felt bolts of guilt: my exceptional academic and professional trajectory granted me an outsider’s look into my own circumstances and my literacy in political and historical texts gave me the tools to kickstart my journey in justice, truth and healing. But there’s no one on this journey with me. It felt meaningless by myself.

Here, I think, I formed the foundation of my practice as an artist and as a person: from then on, I vowed that to the best of my ability, I would never turn my back to my community again, and that when possible, I would always tell the truth.

Love,

Samboleap

He paused for a bit. Never vocal about racist experiences in his time in Sydney, it was rare to hear him so startled. “He makes it sound like it’s not about your talent or your work,” he said quietly.